The Naked Gun Review and Ending Explained

The new Naked Gun reboot, directed by Akiva Schaffer with a script from Dan Gregor, Doug Mand, and Schaffer himself, feels like both a love letter and a bold experiment. On paper, it’s the revival of Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker’s legendary Police Squad! franchise, but in practice it’s this wildly chaotic blend of slapstick, meta-jokes, and social satire.

Produced by Seth MacFarlane, it aims to bring the same energy of Leslie Nielsen’s Drebin into a world of self-driving cars, billionaire conspiracies, and—believe it or not—Clippy. Yeah, that Clippy.

Story Recap, Synopsis, and Review

Now, if you’re wondering what the actual story is, let me break it down the way cinephiles like us crave. This is not just a parody—it’s a parody with a mythology.

The film sets up Frank Drebin Jr., son of the original deadpan disaster-cop, in a case that spirals from a bank robbery to an apocalyptic conspiracy involving a weaponized frequency machine called the P.L.O.T. Device. Yes, they know exactly what they’re doing with that name.

What’s fascinating is how the film manages to maintain the Naked Gun DNA of pratfalls and dumb genius while also sneaking in layers about legacy, parodying tech billionaires, and poking fun at narrative conventions themselves.

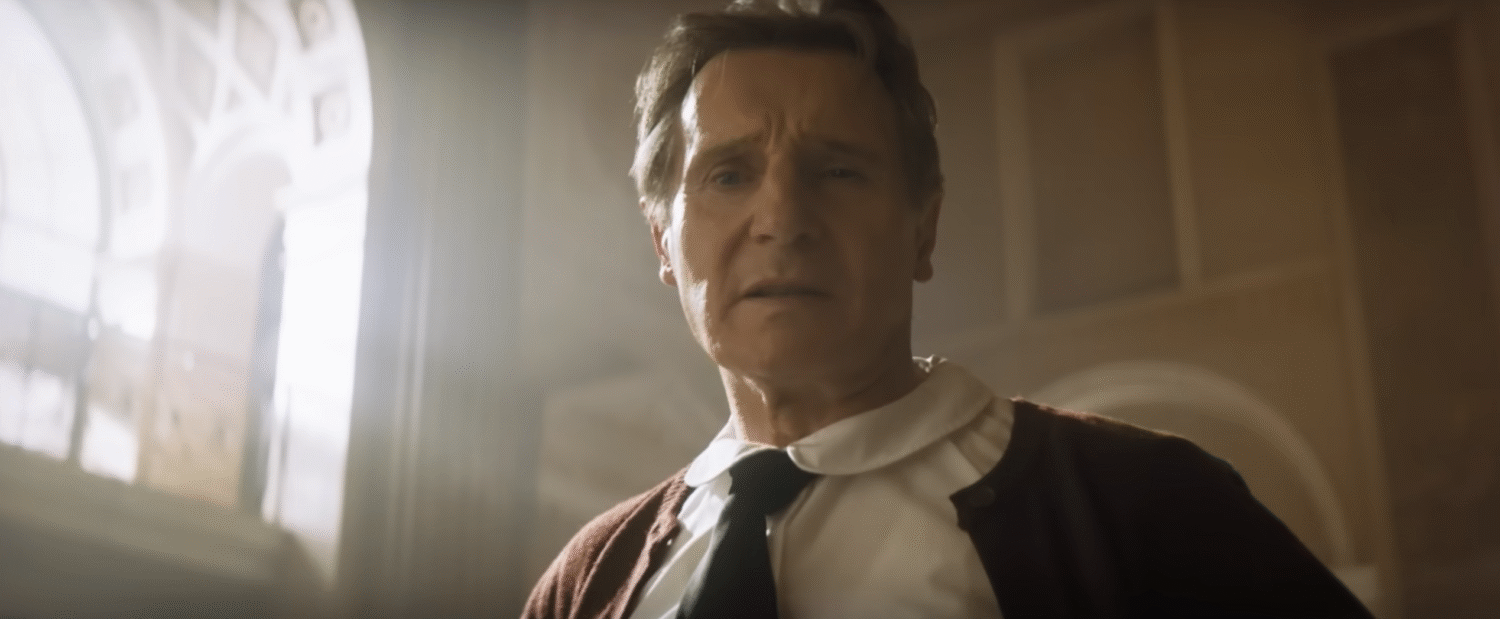

The opening scene says everything about what the movie’s up to. We see Drebin Jr. dressed as a Girl Scout walking into a bank heist.

He unmasks, drops the line, “Frank Drebin, a new version,” and then proceeds to bungle his way through beating criminals in ways so ludicrous that it somehow works.

It’s not just a gag—it’s a statement. The film is telling us: this is a reboot, we’re aware of it, and we’re going to lean into it.

That wink to the audience carries through the whole story. Things start spiraling with Simon Davenport’s supposed “suicide,” which Drebin knows is fishy.

The matchbook clue leading to Richard Cane’s nightclub is classic noir setup, but twisted into Zucker-style absurdity. Cane is a billionaire CEO with a plan so over-the-top it might have been rejected from a Bond villain brainstorm.

He plans to use the P.L.O.T. Device to trigger mass violence, let society collapse, and then emerge from a bunker with his fellow elites to run the world.

And the fact that they book Weird Al Yankovic for bunker entertainment? That’s the Zucker DNA again—mixing absurd non-sequiturs with actual satirical sting.

If you know your Dr. Strangelove, you can see the lineage here. Now, one of my favorite things about how this story is structured is how Drebin stumbles through all of this not because he’s clever, but because the world bends around his incompetence.

The interrogation scenes, where he accidentally incriminates himself while trying to squeeze information out of a criminal, feel like spiritual callbacks to the original franchise.

Nielsen’s blank delivery sold lines that should never have worked. The reboot updates that formula with tech: drones, hacked self-driving cars, and biometric surveillance, all turned into setups for physical comedy.

Think of the car sequence—Cane hijacks Drebin’s electric smart car, and Drebin smashes out the windshield to escape, only to immediately be sealed in again by balloons, bees, and workers carrying a perfectly fitting windshield.

It’s Looney Tunes logic in the body of a modern action set piece. But what makes this work for cinephiles like us isn’t just the gags—it’s the way the film balances parody with genuine narrative stakes.

Beth Davenport, Simon’s sister, isn’t just a damsel. She’s written as this noir archetype who keeps slipping into parody territory—her overly dramatic singing at the nightclub, for example—but she also grounds the story emotionally.

Her grief for Simon and her desire for revenge give Frank something to bounce against. Their romance, while satirical, still carries some heart.

The bit where Gustafson misinterprets their thermal heat signatures as bizarre perversion? That’s straight Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker absurdity.

It only works because we’re invested enough in Frank and Beth to laugh at the misunderstanding rather than dismiss it.

Ending Explained

Now, let’s talk about the ending, because this is where the reboot really flexes its meta-muscles.

The climax takes place at the New Year’s Eve countdown, with massive balls dropping that secretly contain the P.L.O.T. Device. Drebin climbs inside one, loses his pants, and flashes the entire crowd.

In any other movie, that would just be slapstick. Here, it’s thematically loaded.

By losing his pants in front of thousands, Drebin literally loses authority—nobody takes him seriously enough to evacuate when he warns them.

It’s a gag, sure, but it’s also a satirical jab at the loss of credibility in institutions and authority figures in our current age.

When the P.L.O.T. Device goes off and the crowd erupts into chaos, it’s not just violence for comedy’s sake. It’s a sendup of how fragile the social order really is, especially when manipulated by those in power.

The owl? Oh, that’s brilliant. Earlier, Frank jokes that he wants a sign from his father as an owl, and in the climax, an actual owl shows up, literally shitting on Cane to save the day.

It’s absurd, but it’s also the kind of callback humor that ties the whole story together. Frank looks for guidance, finally receives it, and that guidance is both helpful and humiliating.

It’s both slapstick and sincere. That blend is why the ending feels surprisingly satisfying, even when Dave Bautista randomly shows up to cover for Frank’s bathroom break.

The baton-passing moment to Bautista is pure Zucker madness—it interrupts the climax, mocks Hollywood’s obsession with recasting franchises, and then literally throws him to the mob.

If you’ve studied parody structure, you’ll see how layered that gag is. What I also love is how the resolution doesn’t just wrap things up with “bad guy defeated.”

Beth nearly takes her revenge shot, and Frank convinces her not to. That’s parody shading into sincerity again—the classic noir heroine tempted by vengeance, subverted by slapstick but ultimately resolved with a moral core.

Then they use the P.L.O.T. Device itself, flipping it from a tool of destruction into a tool of peace. That inversion isn’t just neat storytelling; it’s meta-commentary on the device’s name.

The plot device that caused chaos now literally resolves the plot. That’s clever writing, the kind of gag you appreciate more the deeper you think about it.

And the Weird Al post-credits scene? Chef’s kiss. Alone in a bunker, strumming away to no one, it’s the perfect absurdist button.

It reminds us that no matter how “high stakes” the plot felt, this is still a comedy franchise that exists to make fun of movies themselves.

Just like Airplane! wasn’t just about a doomed flight but about the disaster genre as a whole, this Naked Gun is about our reboot-heavy, tech-obsessed blockbuster culture—and it skewers it mercilessly.

So what’s my takeaway? This reboot works because it understands parody as more than just reference-dropping.

It builds a world where absurdity is logical, where pratfalls expose cultural truths, and where even an owl’s poop can be cathartic.

If you’re a cinephile, there’s so much to chew on here—from the way it plays with narrative conventions, to how it handles legacy characters, to how it mocks billionaire tech dystopias while still delivering physical comedy at Zucker speed.

It’s messy, it’s chaotic, and sometimes it’s just dumb—but that’s exactly what makes it such a smart revival.