East of Wall Review and Ending Explained

Every now and then, a film comes along that’s hard to categorize—half documentary, half drama, part family story, part cultural portrait. Kate Beecroft’s East of Wall is one of those rare hybrids. It’s rough around the edges, intimate, sometimes frustrating, but it’s also alive in a way that polished Hollywood dramas rarely are.

Story Recap, Synopsis, and Review

So let’s unpack what this thing is doing.

The movie sets us down in the Badlands of South Dakota, where Tabatha (Tabatha Zimiga) is trying to hold her world together after the death of her husband. Right away, you can feel the weight pressing on her: a ranch to maintain, kids to raise (hers and others who’ve drifted into her orbit), and a business that’s bleeding money. It’s less “farm as pastoral escape” and more “farm as endless survival loop.”

Now, the really interesting thing here is how Beecroft builds the story. She doesn’t give us a tight, three-act structure where the obstacles and payoffs are clean. Instead, it’s messy—like life. We meet Porshia (Tabatha’s daughter) who narrates off and on, kind of like a Greek chorus, but in a sporadic, “oh right, she’s telling the story” way. At first, it feels disorienting, but then it clicks: this is a story about how memory and perspective weave in and out, not some straightforward chronicle.

The ranch becomes a sanctuary for kids who don’t have stable homes.

Some of their parents are absent, others are incarcerated, and Tabatha steps in as this accidental matriarch. But she’s not romanticized. She’s exhausted, broke, snapping between tenderness and frustration.

If this were a Hollywood drama, she’d probably get a tidy redemption arc where she saves the kids, the ranch, and herself. Beecroft doesn’t let her off that easy. The power of East of Wall is that it refuses to sanitize the contradictions of caregiving under impossible circumstances.

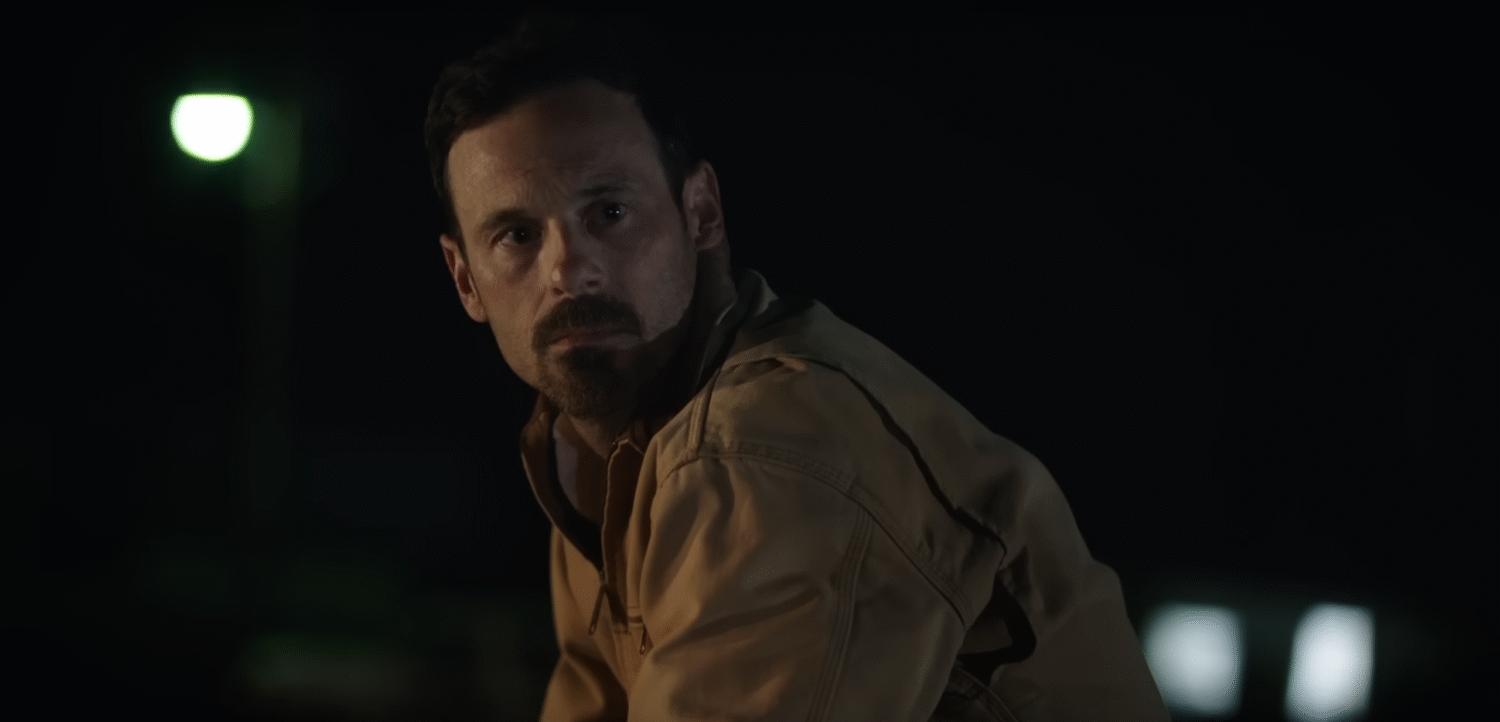

Of course, there’s the outside force: Roy Waters (Scoot McNairy), a businessman who offers to buy the ranch. He’s not a moustache-twirling villain.

He respects Tabatha, admires her connection to horses, and frames his deal as a partnership. This is crucial, because the movie avoids setting up some simple “good woman vs. evil capitalist” binary.

Instead, Roy becomes the embodiment of systemic pressures: the kind of man who can afford to swoop in because the system was already rigged in his favor.

Then you have Tabatha’s mother, Tracey (Jennifer Ehle), chain-smoking and moonshine-swigging, offering chaotic wisdom that cuts deep. She’s messy but magnetic, and her birthday scene—the women’s circle by the fire—hits like a sucker punch.

Real women telling real stories of trauma, survival, and resilience. Some critics called it overacted. I didn’t buy that. To me, it felt like lived-in truth, messy pauses and all. You could practically feel the silence in the theater during that scene, like everyone had been collectively winded.

Now, let’s talk about the horses, because this is where the metaphorical juice of the film lives. Horses in East of Wall aren’t just animals—they’re mirrors. Roy calls one horse “a hole,” meaning it’s broken, damaged, maybe unfixable.

Tabatha sees something else. She works with these animals the way she works with people: through patience, presence, and instinct. The horses become a stand-in for her kids, her family, even herself.

She knows how to heal them, but she’s not sure how to heal herself.

This is where Beecroft flexes her doc-fiction hybrid style. Some of the footage—TikTok videos from the kids, drone shots over the Badlands, scrappy handheld camerawork—feels pulled from life rather than staged.

That’s intentional. It roots the film in lived experience rather than cinematic artifice. Think Nomadland or The Rider—films that blur the line between narrative and documentary, creating this strange authenticity that’s both raw and artful.

But here’s the rub: the structure is messy.

Some critics hated this, calling it unfocused, meandering, or boring. And yeah, if you’re expecting a classic horse-movie arc (Seabiscuit, Secretariat), you’re going to be disappointed. But if you step back and look at the form, you realize that Beecroft is experimenting with what it means to capture grief in cinema.

Grief doesn’t move in clean beats. It drags, circles back, loses focus. The movie is mirroring that very process.

Ending Explained

Alright, let’s get into the part everyone walks out of the theater buzzing about: the ending. Because East of Wall doesn’t give us closure in the traditional sense. Instead, it leaves us in a space that’s both unresolved and quietly devastating.

Near the end, Roy’s offer hangs in the air. He wants the land, he wants Tabatha’s expertise, and he’s dangling stability in front of her. But what the film makes clear is that this deal isn’t really about land at all—it’s about Tabatha herself. The ranch, the horses, the family she’s patched together—those things can’t exist without her. Roy isn’t buying acres of South Dakota dirt. He’s buying her labor, her knowledge, her soul.

And that realization is crushing. Because Tabatha knows it too. The movie doesn’t spell out whether she accepts or rejects the offer. Instead, it forces us to sit with the ambiguity. On the one hand, selling could mean security for her and the kids. On the other hand, it would mean giving herself over to a system that has already taken so much.

The final images aren’t a victory lap. They’re more like fragments: Tabatha tending horses, the kids riding across the plains, the land stretching endlessly. It feels circular, like life will go on, struggles and all. No catharsis, no miracle solution. Just continuity.

Now, why does this matter?

Because Beecroft is making a point about how cinema handles survival stories. Hollywood loves to tie a bow on suffering: you overcome the odds, you win the prize, you find redemption. East of Wall rejects that narrative. It’s saying: sometimes survival doesn’t look like winning.

Sometimes it looks like enduring, holding it together one more day, finding scraps of beauty in the chaos.

Think of Chloé Zhao’s Nomadland—how it ended with Fern returning to the road, not settling down. Or Kelly Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy, where the dog is safe but Wendy is still broke and alone.

These endings sting because they’re true to the world they portray. East of Wall belongs in that lineage.

And let’s not forget the thematic layering of generational trauma.

The women’s circle scene, Tracey’s monologue, Porshia’s narration—it’s all about how pain and resilience get passed down. The ending leaves us with a daughter watching her mother fight to keep it all together.

The implication is that Porshia’s generation will inherit both the burden and the strength. That’s heavy. But it’s real.

Why This Ending Works (Even If It Frustrates)

I get why some viewers walked out pissed. It’s slow, it’s unresolved, it feels like you’ve been asked to sit through someone’s messy life without payoff. But here’s the thing: that’s the point.

Beecroft isn’t serving us entertainment; she’s serving us witness.

She’s asking: what does it mean to observe a woman holding a community together with spit and stubbornness?

That unresolved ending is an invitation to reflect, not consume. It’s asking us to think about the economic systems that push people like Tabatha to the edge.

It’s asking us to notice the beauty and fragility of land that’s always at risk of being commodified. And it’s asking us to honor the resilience of women who hold families—blood or chosen—together even when it costs them everything.

To me, that’s dope AF.

Because it shows cinema can be more than story; it can be presence.

Final Thoughts

East of Wall isn’t for everyone.

If you want slick storytelling, cathartic arcs, and glossy production, you’ll probably be miserable. But if you’re open to cinema that feels like a living document—part grief study, part cultural snapshot, part survival hymn—then there’s something here that sticks with you.

The ending, unresolved as it is, forces us to confront the realities that most films gloss over. Survival isn’t sexy. Grief doesn’t end. Land isn’t just property; it’s identity. And sometimes, choosing to stay, to endure without closure, is the fiercest act of all.

So yeah, it’s flawed, it drags, and it’s messy. But so is life. And in that sense, East of Wall may be one of the most honest films you’ll see this year.